History of art - Perspective

Art Before Perspective

The system of perspective we take for granted today is a relatively recent discovery in artistic history. Before the 14th Century little to no attempts were made to realistically depict the three dimensional world in art in the way in which we are now accustomed to seeing it.

The art of the Byzantine, Medieval and Gothic periods was rich and beautiful, but the images made no attempt to create the illusion of depth and space.

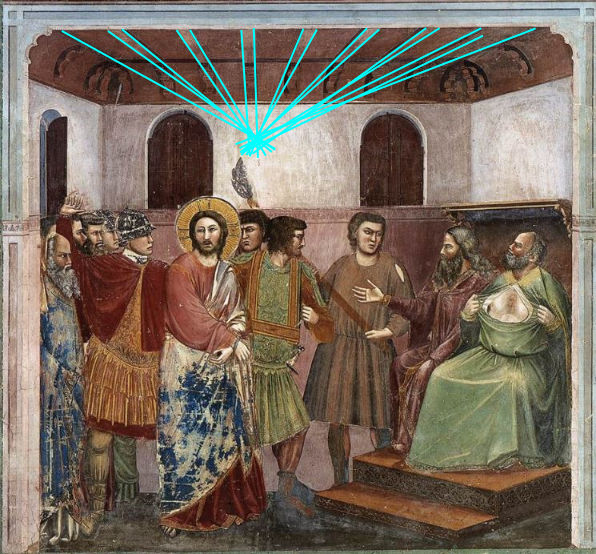

The Italian masters Giotto (c. 1267 – 1337) and Duccio (c. 1255-1260 – c. 1318-1319) began to explore the idea of depth and volume in their art and can be credited with introducing an early form of perspective, using shadowing to great effect to create an illusion of depth, but it was still far from the kind of perspective we are used to seeing in art today.

Christ Before Caiaphas Giotto c. 1305 Fresco, 200 x 185 cm. Scrovegni (Arena) Chapel, Padua, Italy

Last Supper Duccio di Buoninsegna c. 1308–1311 Tempera on wood, 50 x 53 cm. Museo dell'Opera Metropolitana del Duomo, SienaFirst Perspective – Fillipo Brunelleschi & Masaccio

Filippo Brunelleschi was a designer from Italy and an important figure in architecture, he is known to be the first modern engineer, organizer, and only construction supervisor. He is also one of the founding fathers of the Renaissance. Generally, he's well known for creating methods for linear viewpoint for building and in art, constructing the Dome of the famous Florence Cathedral. By greatly depending on geometry and mirrors, to "support Christian spiritual reality", his construction of a linear viewpoint oversaw graphic representation of the space until the late 19th. It also had the deepest and most unexpected influence on the growth of modern science. Many of his accomplishments include other works of architecture, sculpture, math, engineering, and ship design. His main projects are institute in Florence, Italy, and have survived until now. Sadly, his original two linear viewpoint panels were missing.

Florence Cathedral (Italian: Duomo di Firenze)

Filippo Brunelleschi, drawing of the elevation of Santo Spirito, 1428–81, Florence, Italy

Filippo Brunelleschi, drawing of the elevation of Santo Spirito, 1428–81, Florence, Italy

Masaccio, Holy Trinity, c. 1427, fresco (Santa Maria Novella, Florence; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0In this fresco, the ceiling arches shrink as they recede, and figures in the foreground appear larger than those in the middle ground. Together, these elements create a strong sense of depth and three-dimensionality, making this an excellent example of One Point Perspective. Overlaying a perspective grid shows how the artist carefully placed each element to enhance this effect.

Fresco painting by Raphael created for one of the Vatican walls. The School of Athens (1510 - 1511)

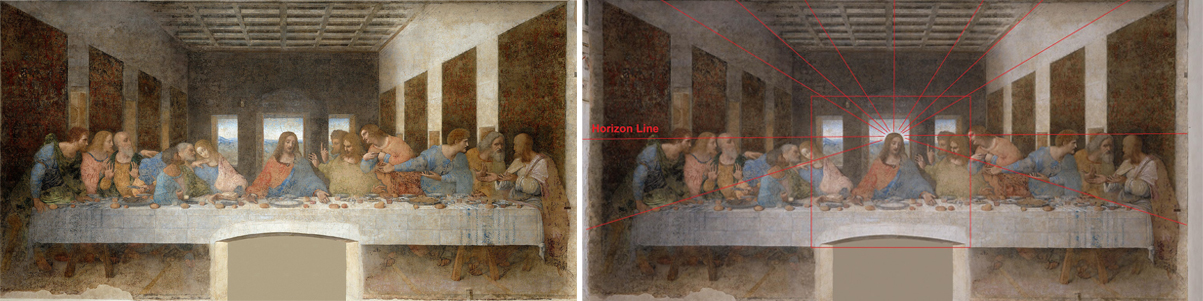

Leonardo balanced the perspective in The Last Supper by placing its vanishing point at Christ's right temple, highlighting the central point of his brain. Radial lines from this point guided the layout of the table, floor lines, and ceiling coffers, while diagonal lines marked the horizontal rows in the ceiling.

Known for his love of symmetry, Leonardo arranged the painting horizontally, with an equal number of figures on each side of Jesus. This precise perspective and symmetry emphasize both the architectural structure and the balanced placement of figures.

Leonardo da Vinci: Last Supper Last Supper, wall painting by Leonardo da Vinci, c. 1495–98, after its 1999 restoration; in Santa Maria delle Grazie, Milan.

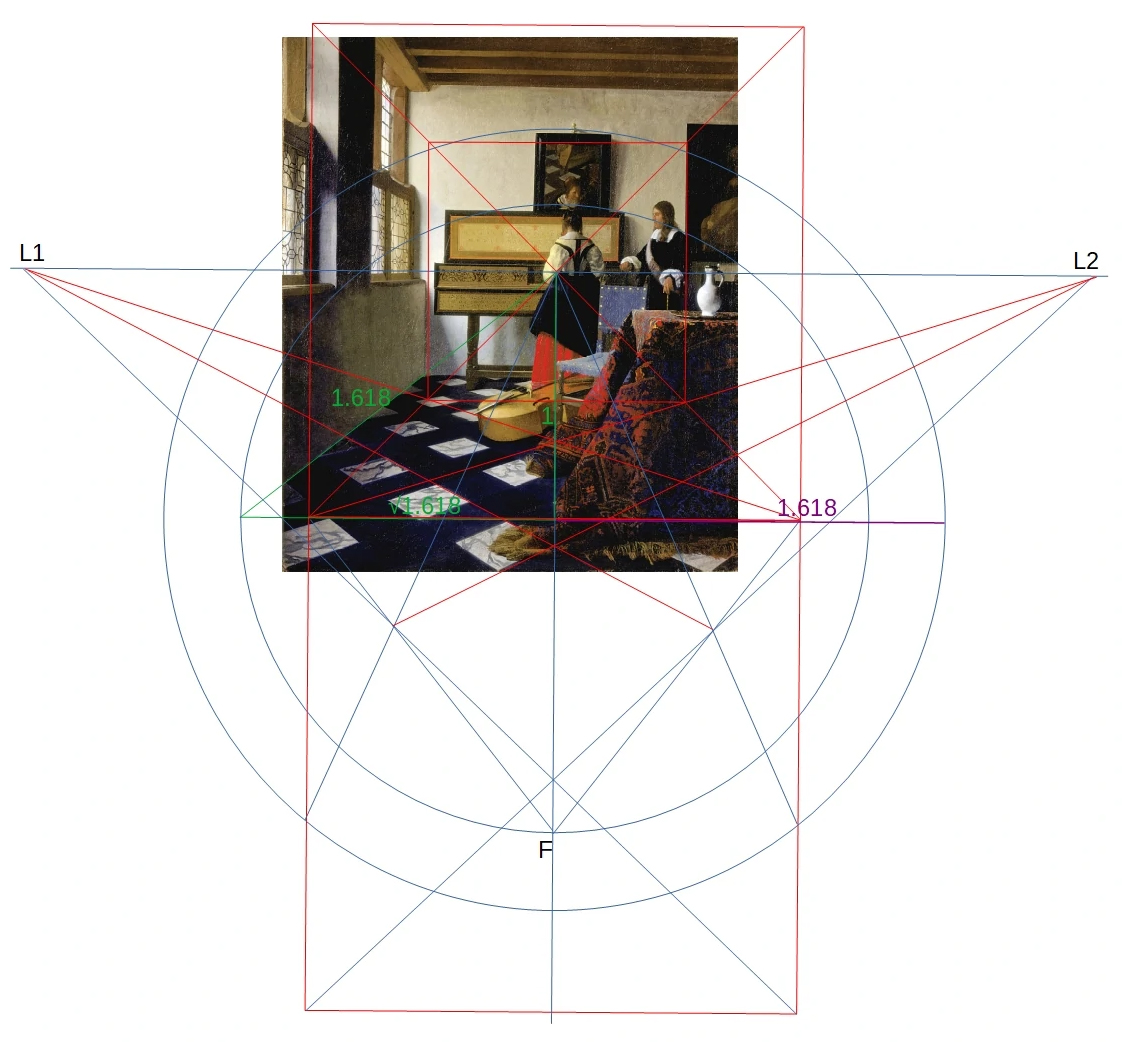

Vermeer was praised by his contemporary art lovers for his mastery of perspective, he was a master of capturing moments, achieving better effects than any camera can do today. Many people tried to copy his painting technique, but the results were always unconvincing. It is the sacred geometry and the Renaissance perspective system that stands behind the eternal effect of his paintings.

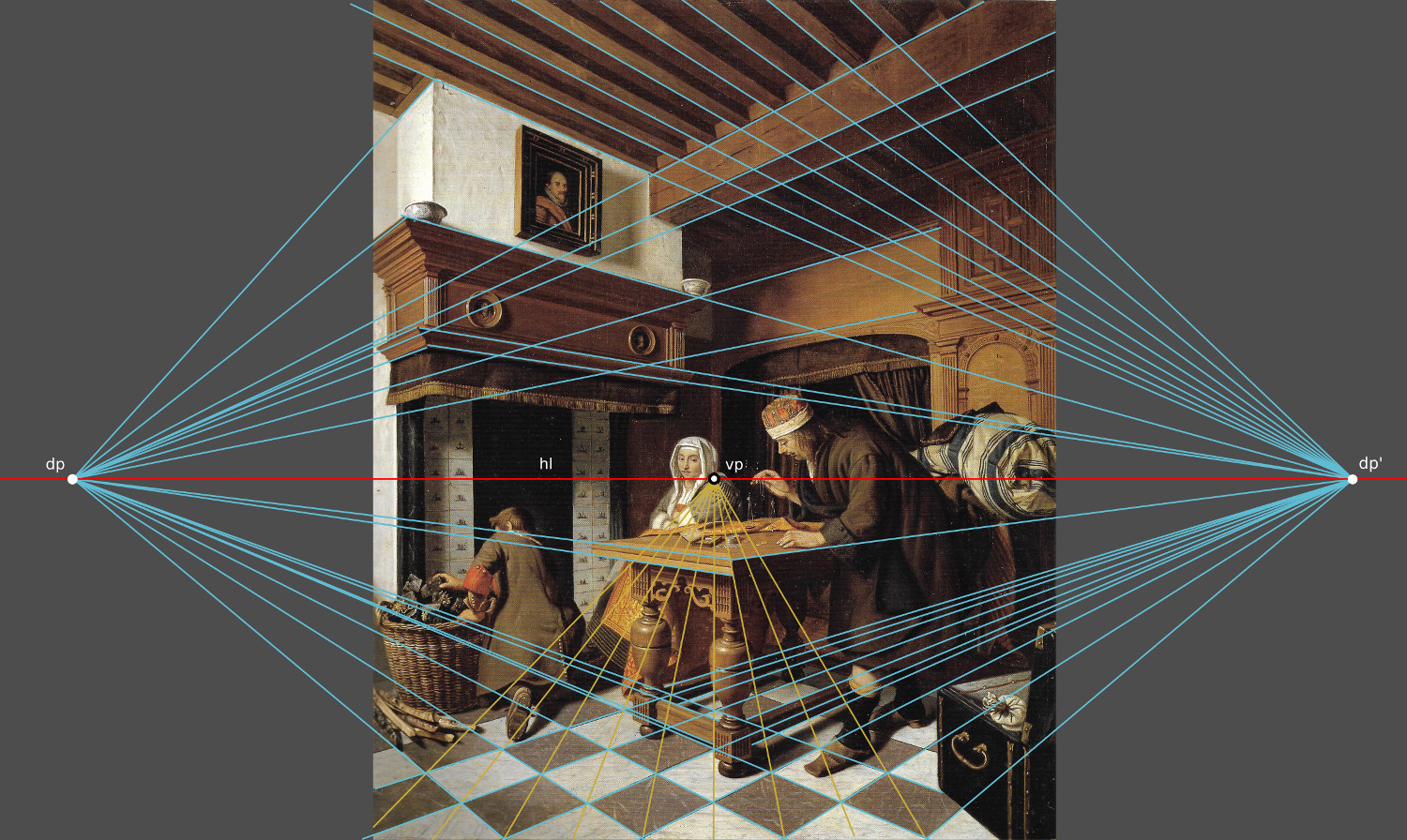

The Music Lesson(De muziekles) c. 1662–1664 Oil on canvas, 73.3 x 64.5 cm. The Royal Collection, The Windsor Castle inv.Creating a precise perspective drawing from scratch is challenging, yet in Cornelis de Man's paintings—The Chess Players and The Goldweigher—we can observe linear perspective. In The Chess Players, all construction lines accurately converge at their vanishing points, while in The Goldweigher, the vanishing lines of a black chest miss the horizon, likely due to a late addition to cover floor tile distortions.

Cornelis de Man, The Gold Weigher 1670-1675 Oil on canvasPainted in 1877 by Gustave Caillebotte, Paris Street; Rainy Day captures Paris’s shift from an ancient city to a modern metropolis. Using a blend of Impressionist themes and classical techniques, it represents change in both art and urban life. Caillebotte, trained at Paris’s École des Beaux-Arts, was drawn to the Impressionists, who sought to depict ordinary people and everyday life rather than traditional subjects.

The painting shows a busy six-point intersection, now known as Place de Dublin, featuring middle-class Parisians under umbrellas. Caillebotte’s precise brushwork and organized perspective reflect his classical training, while his cropped framing was likely inspired by photography, freezing a moment in time. Despite his Impressionist associations, Caillebotte retained a unique style and has been called “an Impressionist in name only.

Gustave Caillebotte: Paris Street; Rainy Day Paris Street; Rainy Day, oil on canvas by Gustave Caillebotte, 1877; in the Art Institute of Chicago